가톨릭 신앙생활 Q&A 코너

|

[꼭필독] 지성덕들과 전통적 교육체계 외 [교리용어_지성덕][_arts][_prudence][_현명][_기술][_언어학][_수학][_논리학][_철학] wisdom |

|---|

|

2013-07-23 ㅣ No.1421

당부의 말씀: [이상, 2021년 8월 25일자 내용 추가 끝] 상당히 오래 전에, 의 본문 전문을 전달해 드립니다.

Good habits of the mind, enabling it to be a more efficient instrument of knowledge. They are distinguished from the moral virtues, since they do not, as such, make one a better person. They make one more effective in the use of what he or she knows and, to that extent, contribute to the practice of moral virtue. According to Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas, there are five intellectual virtues: three pertaining to the theoretical or speculative intellect concerned with the contemplation of the true; and two pertaining to the practical intellect, concerned with the two forms of action, making and doing.

The three speculative intellectual virtues are understanding, science, and wisdom. Understanding (Greek nous, intuitive mind) is the habit of first principles. It is the habitual knowledge of primary self-evident truths that lie at the root of all knowledge. Science (Greek episteme, knowledge) is the habit of conclusions drawn by demonstration from first principles. It is the habitual knowledge of the particular sciences. Wisdom (Greek sophia, wisdom) is the habit of knowing things in their highest causes. It is the organized knowledge of all principles and conclusions in the truth called philosophy.

The two practical intellectual virtues are art and prudence. Art (Greek techne, craftsmanship) is the habit of knowing how to make things, how to produce some external object. As a practical virtue, it includes the mechanical and fine arts and most liberal arts. Prudence (Greek phronesis, practical wisdom) is the habit of knowing how to do things, how to direct activity that does not result in tangible products. It enables one to live a good human life and is the only one of the intellectual virtues that cannot exist apart from the moral virtues.

Originally the program of studies in the Middle Ages, suited for free men. They had been first proposed by Plato in the Republic (III) and adopted by Christian educators as the foundation for more specialized study in law, medicine, and theology. There were seven liberal arts, divided into the trivium and quadrivium.

자유인에게 어울리는 기술(교양 과목, liberal arts, 自由人에게 어울리는 技術)들

The three primary branches in medieval education: grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic (logic). (Etym. Latin tres, three + viae, ways: trivium, crossroad.)

세 개의 과목들(trivium)

The more advancaed program in medieval liberal arts education (beyond the trivium), namely arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. (Etym. Latin quatuor, four + viae, ways: quadrivium.)

네 개의 과목들(quadrivium)

It is desirable, for several reasons, to treat the system of the seven liberal arts from this point of view, and this we propose to do in the present article. The subject possesses a special interest for the historian, because an evolution, extending through more than two thousand years and still in active operation, here challenges our attention as surpassing both in its duration and its local ramifications all other phases of pedagogy. But it is equally instructive for the philosopher because thinkers like Pythagoras, Plato, and St. Augustine collaborated in the framing of the system, and because in general much thought and, we may say, much pedagogical wisdom have been embodied in it. [그러나, 피타고라스(Phythagoras), 플라톤(Plato), 그리고 성 아우구스티노(St. Augustine) 같은 사색가들이 이 체계의 틀을 잡는 데에 협력하였기 때문에, 그리고 일반적으로 많은 사고, 그리고 많은 교육학적 지혜가 그 안에서 구체화되었다고 우리가 말할 수도 있기 때문에, 철학자에게 동등하게 교육적입니다.] Hence, also, it is of importance to the practical teacher, because among the comments of so many schoolmen on this subject may be found many suggestions which are of the greatest utility. [따라서, 실천적 선생(the practical teachers)들에게 중요한데, 왜냐하면 이러한 주제에 대한 너무도 많은 스콜라 학자들의 주석들 중에서 가장 커다랗게 유용한 많은 제안들이 발견될 수도 있기 때문입니다.]

The Oriental system of study, which exhibits an instructive analogy with the one here treated, is that of the ancient Hindus still in vogue among the Brahmins. In this, the highest object is the study of the Veda, i.e. the science or doctrine of divine things, the summary of their speculative and religious writings for the understanding of which ten auxiliary sciences were pressed into service, four of which, viz. phonology, grammar, exegesis, and logic, are of a linguistico-logical nature, and can thus be compared with the Trivium; while two, viz. astronomy and metrics, belong to the domain of mathematics, and therefore to the Quadrivium. The remainder, viz. law, ceremonial lore, legendary lore, and dogma, belong to theology. Among the Greeks the place of the Veda is taken by philosophy, i.e. the study of wisdom, the science of ultimate causes which in one point of view is identical with theology. "Natural Theology", i.e. the doctrine of the nature of the Godhead and of Divine things, was considered as the domain of the philosopher, just as "political theology" was that of the priest, and "mystical theology" of the poet. [See O. Willmann, Geschichte des Idealismus (Brunswick, 1894), I, sect. 10.] Pythagoras (who flourished between 540 B.C. and 510 B.C.) first called himself a philosopher, but was also esteemed as the greatest Greek theologian. The curriculum which he arranged for his pupils led up to the hieros logos, i.e. the sacred teaching, the preparation for which the students received as mathematikoi, i.e. learners, or persons occupied with the mathemata, the "science of learning" — that, in fact, now known as mathematics. The preparation for this was that which the disciples underwent as akousmatikoi, "hearers", after which preparation they were introduced to what was then current among the Greeks as mousike paideia, "musical education", consisting of reading, writing, lessons from the poets, exercises in memorizing, and the technique of music. The intermediate position of mathematics is attested by the ancient expression of the Pythagoreans metaichmon, i.e. "spear-distance"; properly, the space between the combatants; in this case, between the elementary and the strictly scientific education. Pythagoras is moreover renowned for having converted geometrical, i.e. mathematical, investigation into a form of education for freemen. (Proclus, Commentary on Euclid, I, p. 19, ten peri ten geometrian philosophian eis schema paideias eleutherou metestesen.) "He discovered a mean or intermediate stage between the mathematics of the temple and the mathematics of practical life, such as that used by surveyors and business people; he preserves the high aims of the former, at the same time making it the palaestra of intellect; he presses a religious discipline into the service of secular life without, however, robbing it of its sacred character, just as he previously transformed physical theology into natural philosophy without alienating it from its hallowed origin" (Geschichte des Idealismus, I, 19 at the end). An extension of the elementary studies was brought about by the active, though somewhat unsettled, mental life which developed after the Persian wars in the fifth century B.C. From the plain study of reading and writing they advanced to the art of speaking and its theory (rhetoric), with which was combined dialectic, properly the art of alternate discourse, or the discussion of the pro and con. This change was brought about by the sophists, particularly by Gorgias of Leontium. They also attached much importance to manysidedness in their theoretical and practical knowledge. Of Hippias of Elis it is related that he boasted of having made his mantle, his tunic, and his foot-gear (Cicero, De Oratore, iii, 32, 127). In this way, current language gradually began to designate the whole body of educational knowledge as encyclical, i.e. as universal, or all-embracing (egkyklia paideumata, or methemata; egkyklios paideia). The expression indicated originally the current knowledge common to all, but later assumed the above-mentioned meaning, which has also passed into our word encyclopedia.

Socrates having already strongly emphasized the moral aims of education, Plato (429-347 B.C.) protested against its degeneration from an effort to acquire culture into a heaping-up of multifarious information (polypragmosyne). In the "Republic" he proposes a course of education which appears to be the Pythagorean course perfected. [자신의 저술인 "국가(Republic)" 에서 플라톤(Plato)은 완미하게 된(perfected) 피타고라스의 과정(Pythagorean course)인 것으로 생각되는 교육의 한 과정을 제안합니다.] It begins with musico-gymnastic culture, by means of which he aims to impress upon the senses the fundamental forms of the beautiful and the good, i.e. rhythm and form (aisthesis). The intermediate course embraces the mathematical branches, viz. arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music, which are calculated to put into action the powers of reflection (dianoia), and to enable the student to progress by degrees from sensuous to intellectual perception, as he successively masters the theory of numbers, of forms, of the kinetic laws of bodies, and of the laws of (musical) sounds. This leads to the highest grade of the educational system, its pinnacle (thrigkos) so to speak, i.e. philosophy, which Plato calls dialectic, thereby elevating the word from its current meaning to signify the science of the Eternal as ground and prototype of the world of sense. This progress to dialectic (dialektike poreia) is the work of our highest cognitive faculty, the intuitive intellect (nous). In this manner Plato secures a psychological, or noetic, basis for the sequence of his studies, namely: sense-perception, reflection, and intellectual insight. During the Alexandrine period, which begins with the closing years of the fourth century before Christ, the encyclical studies assume scholastic forms. Grammar, as the science of language (technical grammar) and explanation of the classics (exegetical grammar), takes the lead; rhetoric becomes an elementary course in speaking and writing. By dialectic they understood, in accordance with the teaching of Aristotle, directions enabling the student to present acceptable and valid views on a given subject; thus dialectic became elementary practical logic. The mathematical studies retained their Platonic order; by means of astronomical poems, the science of the stars, and by means of works on geography, the science of the globe became parts of popular education (Strabo, Geographica, I, 1, 21-23). Philosophy remained the culmination of the encyclical studies, which bore to it the relation of maids to a mistress, or of a temporary shelter to the fixed home (Diog. Laert., II, 79; cf. the author's Didaktik als Bildungslehre, I, 9

Among the Romans grammar and rhetoric were the first to obtain a firm foothold; culture was by them identified with eloquence, as the art of speaking and the mastery of the spoken word based upon a manifold knowledge of things. In his "Institutiones Oratoriae" Quintilian, the first professor eloquentiae at Rome in Vespasian's time, begins his instruction with grammar, or, to speak precisely, with Latin and Greek Grammar, proceeds to mathematics and music, and concludes with rhetoric, which comprises not only elocution and a knowledge of literature, but also logical — in other words dialectical — instruction. However, the encyclical system as the system of the liberal arts, or Artes Bonae, i.e. the learning of the vir bonus, or patriot, was also represented in special handbooks. The "Libri IX Disciplinarum" of the learned M. Terentius Varro of Reate, an earlier contemporary of Cicero, treats of the seven liberal arts adding to them medicine and architectonics. How the latter science came to be connected with the general studies is shown in the book "De Architecturâ", by M. Vitruvius Pollio, a writer of the time of Augustus, in which excellent remarks are made on the organic connection existing between all studies. "The inexperienced", he says, "may wonder at the fact that so many various things can be retained in the memory; but as soon as they observe that all branches of learning have a real connection with, and a reciprocal action upon, each other, the matter will seem very simple; for universal science (egkyklios, disciplina) is composed of the special sciences as a body is composed of members, and those who from their earliest youth have been instructed in the different branches of knowledge (variis eruditionibus) recognize in all the same fundamental features (notas) and the mutual relations of all branches, and therefore grasp everything more easily" (Vitr., De Architecturâ, I, 1, 12). In these views the Platonic conception is still operative, and the Romans always retained the conviction that in philosophy alone was to be found the perfection of education. Cicero enumerates the following as the elements of a liberal education: geometry, literature, poetry, natural science, ethics, and politics. [키케로(Cecero)는 다음의 것들을 한 자유인에게 어울리는 교육(a liberal education, 교양 교육)의 요소들로서 열거합니다(enumerates): 기하학(geometry), 문학(literature), 시학(poetry), 자연 과학(natural science), 윤리학(ethics), 그리고 정치학(politics).] (Artes quibus liberales doctrinae atque ingenuae continentur; geometria, litterarum cognito et poetarum, atque illa quae de naturis rerum, quae de hominum moribus, quae de rebus publicis dicuntur.)

Christianity taught men to regard education and culture as a work for eternity, to which all temporary objects are secondary. [그리스도교는 교육과 문화를 영원(eternity)을 위한 한 개의 일(work)로서 존중하도록 사람들을 가르쳤는데, 이 일에 비하여 세속의 대상들 모두는 부차적인 일들 입니다.] It softened, therefore, the antithesis between the liberal and illiberal arts; the education of youth attains its purpose when it acts so "that the man of God may be perfect, furnished to every good work" (2 Timothy 3:17). In consequence, labour, which among the classic nations had been regarded as unworthy of the freeman, who should live only for leisure, was now ennobled; but learning, the offspring of leisure, lost nothing of its dignity. [그 결과, 고전적인 나라들 사이에서, 오로지 자유 시간(leisure)에 전념하여야만 하는 자유인(the freeman)에게 어울리지 않는 것으로서 이미 간주되어 왔던 노동(labour)은 이제 고상하게 되었으나, 그러나 자유 시간(leisure)의 소산인 배움(learning)은 그 품위의 어떠한 것도 잃지 않았습니다.] The Christians retained the expression, mathemata eleuthera, studia liberalia, as well as the gradation of these studies, but now Christian truth was the crown of the system in the form of religious instruction for the people, and of theology for the learned. The appreciation of the several branches of knowledge was largely influenced by the view expressed by St. Augustine in his little book, "De Doctrinâ Christianâ". As a former teacher of rhetoric and as master of eloquence he was thoroughly familiar with the Artes and had written upon some of them. Grammar retains the first place in the order of studies, but the study of words should not interfere with the search for the truth which they contain. The choicest gift of bright minds is the love of truth, not of the words expressing it. "For what avails a golden key if it cannot give access to the object which we wish to reach, and why find fault with a wooden key if it serves our purpose?" (De Doctr. Christ., IV, 11, 26). In estimating the importance of linguistic studies as a means of interpreting Scripture, stress should be laid upon exegetical, rather than technical grammar. Dialectic must also prove its worth in the interpretation of Scripture; "it traverses the entire text like a tissue of nerves" (Per totum textum scripturarum colligata est nervorum vice, ibid., II, 40, 56). Rhetoric contains the rules of fuller discussion (praecepta uberioris disputationis); it is to be used rather to set forth what we have understood than to aid us in understanding [수사학(Rhetoric)은 이해(understanding)에 있어 우리를 돕는 것보다는 오히려 우리가 이미 이해한 바를 꾸미는 데(set forth)에 사용되어져야 합니다] (ibid., II, 18). St. Augustine compared a masterpiece of rhetoric with the wisdom and beauty of the cosmos, and of history — "Ita quâdam non verborum, sed rerum, eloquentiâ contrariorum oppositione seculi pulchritudo componitur" (City of God XI.18). Mathematics was not invented by man, but its truths were discovered; they make known to us the mysteries concealed in the numbers found in Scripture, and lead the mind upwards from the mutable to the immutable; and interpreted in the spirit of Divine Love, they become for the mind a source of that wisdom which has ordered all things by measure, weight, and number [수학(Mathematics)은 사람에 의하여 발명되었던 것이 아니고, 수학의 진리들은 발견되었던 것이며, 그리고 이 진리들은 성경 본문에서 발견되는 숫자들에 감추어져 있는 신비들을 우리에게 알게 하고, 그리고 변하기 쉬운 것들로부터 변하지 않은 것들로 위를 향하여 마음을 인도하며, 그리하여 수학의 진리들은, 신성(神性)적 사랑(divine love, amour divin)(Divine Love)(*)의 정신 안에서 해석되어, 척도(measure), 무게(weight), 그리고 숫자(number)에 의하여 모든 사물들에 이미 순서를 매겨왔던, 마음을 위한 바로 그 지혜(wisdom)의 한 원천(a source)이 됩니다.] (De Doctr. Christ., II, 39, also Wisdom, xi, 21). The truths elaborated by the philosophers of old, like precious ore drawn from the depths of an all-ruling Providence, should be applied by the Christian in the spirit of the Gospel, just as the Israelites used the sacred vessels of the Egyptians for the service of the true God (De Doctr. Christ., II, 41).

----- [내용 추가 일자: 2016년 4월 30일] (*) 번역자 주: 신성(神性)적 사랑(divine love, amour divin)이라는 용어의 정의(definition)는 다음의 글에 있으니 꼭 읽도록 하라: http://ch.catholic.or.kr/pundang/4/soh/1691.htm <----- 필독 권고 [이상, 내용 추가 끝] -----

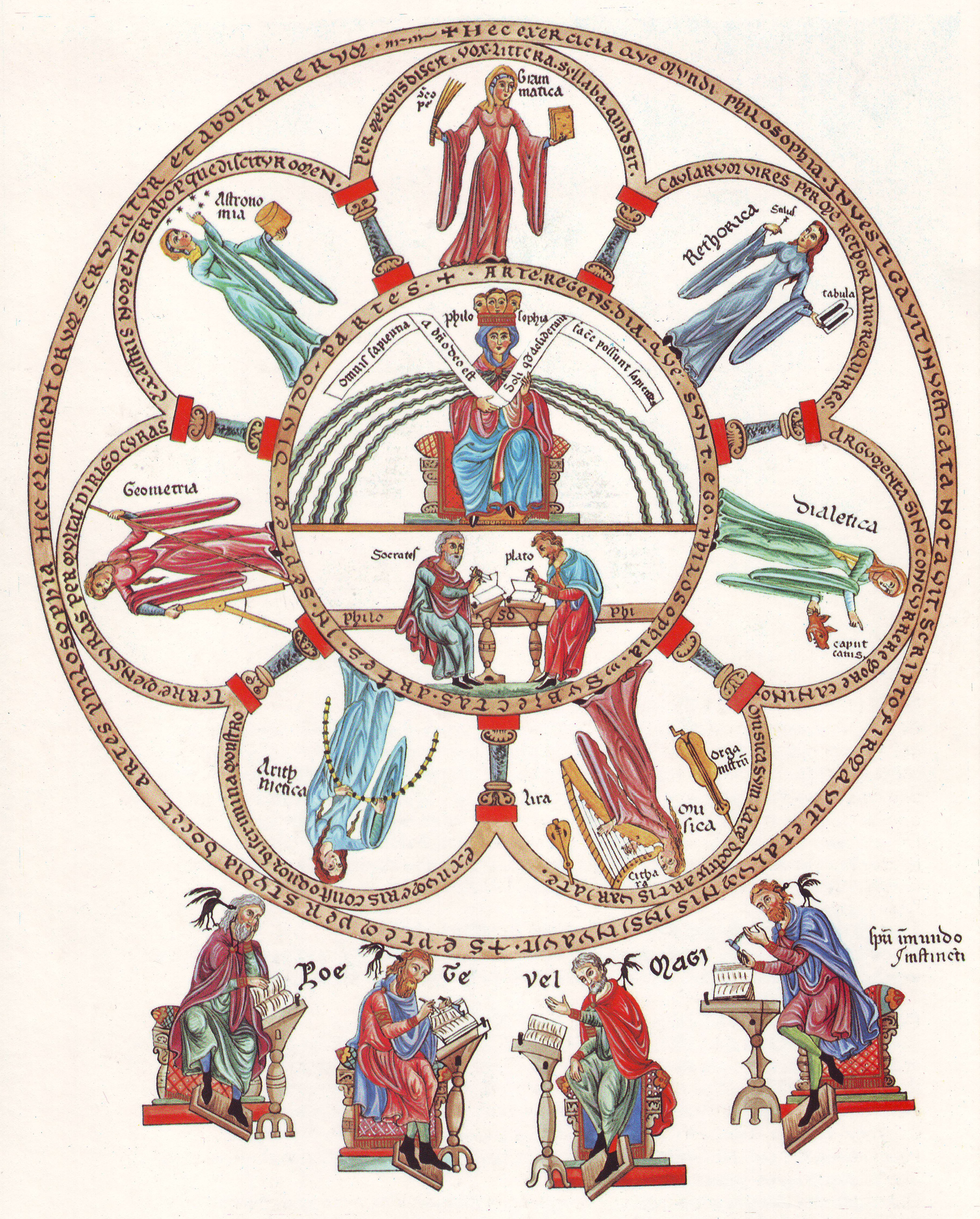

The series of text-books on this subject in vogue during the Middle Ages begins with the work of an African, Marcianus Capella, written at Carthage about A.D. 420. It bears the title "Satyricon Libri IX" from satura, sc. lanx, "a full dish". In the first two books, "Nuptiae Philologiae et Mercurii", carrying out the allegory that Phoebus presents the Seven Liberal Arts as maids to the bride Philology, mythological and other topics are treated. In the seven books that follow, each of the Liberal Arts presents the sum of her teaching. A simpler presentation of the same subject is found in the little book, intended for clerics, entitled, "De artibus ac disciplinis liberalium artium", which was written by Magnus Aurelius Cassiodrus in the reign of Theodoric. Here it may be noted that Ars means "text-book", as does the Greek word techen; disciplina is the translation of the Greek mathesis or mathemata, and stood in a narrower sense for the mathematical sciences. Cassiodorus derives the word liberalis not from liber, "free", but from liber, "book", thus indicating the change of these studies to book learning, as well as the disappearance of the view that other occupations are servile and unbecoming a free man. [카시오도루스(Cassiodorus)는 자유인에게 어울리는 이라는 단어를 [라틴어] liber, "자유의(free)" 로부터가 아니라, [라틴어] liber, "책(book)" 으로부터 도출하며, 그리하여 이러한 방식으로, 다른 직업들이 노예적이며 그리고 자유인에게 어울리지 않다는 견해의 사라짐뿐만이 아니라, 책으로만 배우는 학문(book learning)으로 이들 학습들의 변화를 나타냅니다.] Again we meet with the Artes at the beginning of an encyclopedic work entitled "Origines, sive Etymologiae", in twenty books, compiled by St. Isidore, Bishop of Seville, about 600. The first book of this work treats of grammar; the second, of rhetoric and dialectic, both comprised under the name of logic; the third, of the four mathematical branches. In books IV-VIII follow medicine, jurisprudence, theology; but books IX and X give us linguistic material, etymologies, etc., and the remaining books present a miscellany of useful information. Albinus (or Alcuin), the well-known statesman and counsellor of Charles the Great, dealt with the Artes in separate treatises, of which only the treatises intended as guides to the Trivium have come down to us. In the introduction, he finds in Prov. ix, 1 (Wisdom hath built herself a house, she hath hewn her out seven pillars) an allusion to the seven liberal arts which he thinks are meant by the seven pillars. The book is written in dialogue form, the scholar asking questions, and the master answering them. One of Alcuin's pupils, Rabanus Maurus, who died in 850 as the Archbishop of Mainz, in his book entitled "De institutione clericorum", gave short instructions concerning the Artes, and published under the title, "De Universo", what might be called an encyclopedia. The extraordinary activity displayed by the Irish monks as teachers in Germany led to the designation of the Artes as Methodus Hybernica. To impress the sequence of the arts on the memory of the student, mnemonic verses were employed such as the hexameter; Lingua, tropus, ratio, numerus, tonus, angulus, astra. By the number seven the system was made popular; the Seven Arts recalled the Seven Petitions of the Lord's Prayer, the Seven Gifts of the Holy Ghost, the Seven Sacraments, the Seven Virtues, etc. The Seven Words on the Cross, the Seven Pillars of Wisdom, the Seven Heavens might also suggest particular branches of learning. The seven liberal arts found counterparts in the seven mechanical arts; the latter included weaving, blacksmithing, war, navigation, agriculture, hunting, medicine, and the ars theatrica. To these were added dancing, wrestling, and driving. [일곱 개의, 자유인에게 어울리는, 기술들은 일곱 개의 직업(업무 혹은 일에 있어서의 기술)(the seven mechanical arts)들(*)에서 대응물들을 발견하였으며, 그리고 후자는 피륙짜기(weaving), 대장장이 일(blacksmithing), 전쟁(war), 항해(navigation); 농업(agriculture), 사냥(hunting), 의술(medicine), 그리고 극장 기술(the ars theatrica). 이들에 무용(dancing), 격투(wrestling), 그리고 운전(driving)들이 추가되었습니다.](*) Even the accomplishments to be mastered by candidates for knighthood were fixed at seven: riding, tilting, fencing, wrestling, running, leaping, and spear-throwing. Pictorial illustrations of the Artes are often found, usually female figures with suitable attributes; thus Grammar appears with book and rod, Rhetoric with tablet and stilus, Dialectic with a dog's head in her hand, probably in contrast to the wolf of heresy — cf. the play on words Domini canes, Dominicani — Arithmetic with a knotted rope, Geometry with a pair of compasses and a rule, Astronomy with bushel and stars, and Music with cithern and organistrum. Portraits of the chief representatives of the different sciences were added. Thus in the large group by Taddeo Gaddi in the Dominican convent of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, painted in 1322, the central figure of which is St. Thomas Aquinas, Grammar appears with either Donatus (who lived about A.D. 250) or Priscian (about A.D. 530), the two most prominent teachers of grammar, in the act of instructing a boy; Rhetoric accompanied by Cicero; Dialectic by Zeno of Elea, whom the ancients considered as founder of the art; Arithmetic by Abraham, as the representative of the philosophy of numbers, and versed in the knowledge of the stars; Geometry by Euclid (about 300 B.C.), whose "Elements" was the text-book par excellence; Astronomy by Ptolemy, whose "Almagest" was considered to be the canon of star-lore; Music by Tubal Cain using the hammer, probably in allusion to the harmoniously tuned hammers which are said to have suggested to Pythagoras his theory of intervals. As counterparts of the liberal arts are found seven higher sciences: civil law, canon law, and the five branches of theology entitled speculative, scriptural, scholastic, contemplative, and apologetic. (Cf. Geschichte des Idealismus, II, Par. 74, where the position of St. Thomas Aquinas towards the sciences is discussed.)

An instructive picture of the seven liberal arts in the twelfth century may be found in the work entitled "Didascalicum", or "Eruditio Didascalici", written by the Augustinian canon, Hugo of St. Victor, who died at Paris, in 1141. He was descended from the family of the Counts Blankenburg in the Harz Mountains and received his education at the Augustinian convent of Hammersleben in the Diocese of Halberstadt, where he devoted himself to the liberal arts from 1109 to 1114. In his "Didascalicum", VI, 3, he writes "I make bold to say that I never have despised anything belonging to erudition, but have learned much which to others seemed to be trifling and foolish. I remember how, as a schoolboy, I endeavoured to ascertain the names of all objects which I saw, or which came under my hands, and how I formulated my own thoughts concerning them [perpendens libere], namely: that one cannot know the nature of things before having learned their names. How often have I set myself as a voluntary daily task the study of problems [sophismata] which I had jotted down for the sake of brevity, by means of a catchword or two [dictionibus] on the page, in order to commit to memory the solution and the number of nearly all the opinions, questions, and objections which I had learned. I invented legal cases and analyses with pertinent objections [dispositiones ad invicem controversiis], and in doing so carefully distinguished between the methods of the rhetorician, the orator, and the sophist. I represented numbers by pebbles, and covered the floor with black lines, and proved clearly by the diagram before me the differences between acute-angled, right-angled, and obtuse-angled triangles; in like manner I ascertained whether a square has the same area as a rectangle two of whose sides are multiplied, by stepping off the length in both cases [utrobique procurrente podismo]. I have often watched through the winter night, gazing at the stars [horoscopus — not astrological forecasting, which was forbidden, but pure star-study]. Often have I strung the magada [Gr. magadis, an instrument of 20 strings, giving ten tones] measuring the strings according to numerical values, and stretching them over the wood in order to catch with my ear the difference between the tones, and at the same time to gladden my heart with the sweet melody. This was all done in a boyish way, but it was far from useless, for this knowledge was not burdensome to me. I do not recall these things in order to boast of my attainments, which are of little or no value, but to show you that the most orderly worker is the most skillful one [illum incedere aptissime qui incedit ordinate], unlike many who, wishing to take a great jump, fall into an abyss; for as with the virtues, so in the sciences there are fixed steps. But, you will say, I find in histories much useless and forbidden matter; why should I busy myself therewith? Very true, there are in the Scriptures many things which, considered in themselves, are apparently not worth acquiring, but which, if you compare them with others connected with them, and if you weigh them, bearing in mind this connection [in toto suo trutinare caeperis], will prove to be necessary and useful. Some things are worth knowing on their own account; but others, although apparently offering no return for our trouble, should not be neglected, because without them the former cannot be thoroughly mastered [enucleate sciri non possunt]. Learn everything; you will afterwards discover that nothing is superfluous; limited knowledge affords no enjoyment [coarctata scientia jucunda non est]."

The connection of the Artes with philosophy and wisdom was faithfully kept in mind during the Middle Ages. [철학(philosophy) 및 지혜(wisdom)와 이 기술들의 관계는 중세 동안 충실하게 기억되어졌습니다.] Hugo says of it: "Among all the departments of knowledge the ancients assigned seven to be studied by beginners, because they found in them a higher value than in the others, so that whoever has thoroughly mastered them can afterwards master the rest rather by research and practice than by the teacher's oral instruction. They are, as it were, the best tools, the fittest entrance through which the way to philosophic truth is opened to our intellect. Hence the names trivium and quadrivium, because here the robust mind progresses as if upon roads or paths to the secrets of wisdom. It is for this reason that there were among the ancients, who followed this path, so many wise men. Our schoolmen [scholastici] are disinclined, or do not know while studying, how to adhere to the appropriate method, whence it is that there are many who labour earnestly [studentes], but few wise men" (Didascalicum, III, 3).

St. Bonaventure (1221-74) in his treatise "De Reductione artium ad theologiam" proposes a profound explanation of the origin of the Artes, including philosophy; basing it upon the method of Holy Writ as the method of all teaching. Holy Scripture speaks to us in three ways: by speech (sermo), by instruction (doctrina), and by directions for living (vita). It is the source of truth in speech, of truth in things, and of truth in morals, and therefore equally of rational, natural, and moral philosophy. Rational philosophy, having for object the spoken truth, treats it from the triple point of view of expression, of communication, and of impulsion to action; in other words it aims to express, to teach, to persuade (exprimere, docere, movere). These activities are represented by sermo congruus, versus, ornatus, and the arts of grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric. Natural philosophy seeks the truth in things themselves as rationes ideales, and accordingly it is divided into physics, mathematics, and metaphysics. Moral philosophy determines the veritas vitæ for the life of the individual as monastica (monos alone), for the domestic life as oeconomica, and for society as politica.

To general erudition and encyclopedic learning medieval education has less close relations than that of Alexandria, principally because the Trivium had a formal character, i.e. it aimed at training the mind rather than imparting knowledge. The reading of classic authors was considered as an appendix to the Trivium. Hugo, who, as we have seen, does not undervalue it, includes in his reading poems, fables, histories, and certain other elements of instruction (poemata, fabulae, historiae, didascaliae quaedam). The science of language, to use the expression of Augustine, is still designated as the key to all positive knowledge; for this reason its position at the head of the Arts (Artes) is maintained. So John of Salisbury (b. between 1110 and 1120; d. 1180, Bishop of Chartres) says: "If grammar is the key of all literature, and the mother and mistress of language, who will be bold enough to turn her away from the threshold of philosophy? Only he who thinks that what is written and spoken is unnecessary for the student of philosophy" (Metalogicus, I, 21). Richard of St. Victor (d. 1173) makes grammar the servant of history, for he writes, "All arts serve the Divine Wisdom, and each lower art, if rightly ordered, leads to a higher one. Thus the relation existing between the word and the thing required that grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric should minister to history" (Rich., ap. Vincentium Bell., Spec. Doctrinale, XVII, 31). The Quadrivium had, naturally, certain relations to to the sciences and to life; this was recognized by treating geography as a part of geometry, and the study of the calendar as part of astronomy. We meet with the development of the Artes into encyclopedic knowledge as early as Isadore of Seville and Rabanus Maurus, especially in the latter's work, "De Universo". It was completed in the thirteenth century, to which belong the works of Vincent of Beauvais (d. 1264), instructor of the children of St. Louis (IX). In his "Speculum Naturale" he treats of God and nature; in the "Speculum Doctrinale", starting from the Trivium, he deals with the sciences; in the "Speculum Morale" he discusses the moral world. To these a continuator added a "Speculum Historiale" which was simply a universal history.

For the academic development of the Artes it was of importance that the universities accepted them as a part of their curricula. [이 기술들의 학원에서의 발전을 위하여 대학교들이 그들의 교과 과정들의 한 부분으로서 이 기술들을 인정하였던 것은 중요하였습니다.] Among their ordines, or faculties, the ordo artistarum, afterwards called the faculty of philosophy, was fundamental: Universitas fundatur in artibus. It furnished the preparation not only for the Ordo Theologorum, but also for the Ordo Legistarum, or law faculty, and the Ordo Physicorum, or medical faculty. Of the methods of teaching and the continued study of the arts at the universities in the fifteenth century, the text-book of the contemporary Carthusian, Gregory Reisch, Confessor of the Emperor Maximilian I, gives us a clear picture. He treats in twelve books: (I) of the Rudiments of Grammar; (II) of the Principles of Logic; (III) of the Parts of an Oration; (IV) of Memory, of Letter-writing, and of Arithmetic; (V) of the Principles of Music; (VI) of the Elements of Geometry; (VII) of the Principles of Astronomy; (VIII) of the Principles of Natural Things; (IX) of the Origin of Natural Things; (X) of the Soul; (XI) of the Powers; (XII) of the Principles of Moral Philosophy.-- The illustrated edition printed in 1512 at Strasburg has for appendix: the elements of Greek literature, Hebrew, figured music and architecture, and some technical instruction (Graecarum Litterarum Institutiones, Hebraicarum Litterarum Rudimenta, Musicae Figuratae Institutiones, Architecturae Rudimenta).

At the universities the Artes, at least in a formal way, held their place up to modern times. [대학교들에서 이 기술들은, 적어도 어떤 형식적 방식으로, 자신들의 자리를 근대 시기들에 이르기까지 유지하였습니다.] At Oxford, Queen Mary (1553-58) erected for them colleges whose inscriptions are significant, thus: "Grammatica, Litteras disce"; "Rhetorica persuadet mores"; "Dialectica, Imposturas fuge"; "Arithmetica, Omnia numeris constant"; "Musica, Ne tibi dissideas"; "Geometria, Cura, quae domi sunt"; "Astronomia, Altiora ne quaesieris". The title "Master of the Liberal Arts" is still granted at some of the universities in connection with the Doctorate of Philosophy; in England that of "Doctor of Music" is still in regular use. ["Master of the Liberal Arts(자유인들에게 어울리는 기술들의 석사)" 라는 칭호(title)는 철학 박사 학위(the Doctorate of Philosophy)와 관련하여 대학교들 중의 일부에서 지금까지도(still) 수여되고 있으며, 그리고 영국에서는 "음악 박사(Doctor of Music)" 라는 칭호는 지금까지도 일상적 사용에 있습니다.] In practical teaching, however, the system of the Artes has declined since the sixteenth century. [그러나 실천적 가르침에 있어 이 기술들의 체계는 16세기 이후로 이미 쇠퇴하였습니다.] The Renaissance saw in the technique of style (eloquentia) and in its mainstay, erudition, the ultimate object of collegiate education, thus following the Roman rather than the Greek system. Grammar and rhetoric came to be the chief elements of the preparatory studies, while the sciences of the Quadrivium were embodied in the miscellaneous learning (eruditio) associated with rhetoric. In Catholic higher schools philosophy remained as the intermediate stage between philological studies and professional studies; while according to the Protestant scheme philosophy was taken over (to the university) as a Faculty subject. The Jesuit schools present the following gradation of studies: grammar, rhetoric, philosophy, and, since philosophy begins with logic, this system retains also the ancient dialectic.

In the erudite studies spoken of above, must be sought the germ of the encyclopedic learning which grew unceasingly during the seventeenth century. Amos Comenius (d. 1671), the best known representative of this tendency, who sought in his "Orbis Pictus" to make this diminutive encyclopedia (encyclopædiola) the basis of the earliest grammatical instruction, speaks contemptuously of "those liberal arts so much talked of, the knowledge of which the common people believe a master of philosophy to acquire thoroughly", and proudly declares, "Our men rise to greater height". (Magna Didactica, xxx, 2.) His school classes are the following: grammar, physics, mathematics, ethics, dialectic, and rhetoric. In the eighteenth century undergraduate studies take on more and more the encyclopedic character, and in the nineteenth century the class system is replaced by the department system, in which the various subjects are treated simultaneously with little or no reference to their gradation; in this way the principle of the Artes is finally surrendered. [19세기에 과목 체계는, 그 안에서 다양한 주제들이 그들의 단계적 변화에 대한 거의 혹은 아무런 언급 없이 동시에 다루어지는, 학과 체계에 의하여 대체되며, 그리하여 바로 이러한 방식으로 이 기술들의 원리는 최종적으로 버려지게 됩니다.] Where, moreover, as in the Gymnasia of Germany, philosophy has been dropped from the course of studies, miscellaneous erudition becomes in principle an end unto itself. Nevertheless, present educational systems preserve traces of the older systematic arrangement (language, mathematics, philosophy). [그럼에도 불구하고, 현재의 교육 체계들은 가장 오래된 체계젹인 배열을 보존하고 있습니다 (언어학, 수학, 철학).] In the early years of his Gymnasium course the youth must devoted his time and energy to the study of languages, in the middle years, principally to mathematics, and in his last years, when he is called upon to express his own thoughts, he begins to deal with logic and dialectic, even if it be only in the form of composition. He is therefore touching upon philosophy. This gradation which works its own way, so to speak, out of the present chaotic condition of learned studies, should be made systematic; the fundamental idea of the Artes Liberales would thus be revived.

The Platonic idea, therefore, that we should advance gradually from sense-perception by way of intellectual argumentation to intellectual intuition, is by no means antiquated. [그러므로, 감각-인식(sense-perception)으로부터 지성적 논증(intellectual argumentation)을 거쳐서 지성적 직관(intellectual intuition)으로 점진적으로 우리가 전진하여야 한다는 플라톤의 이상(the Platonic idea)은 결코 한물가게 된 것이 아닙니다.] Mathematical instruction, admittedly a preparation for the study of logic, could only gain if it were conducted in this spirit, if it were made logically clearer, if its technical content were reduced, and if it were followed by logic. The express correlation of mathematics to astronomy, and to musical theory, would bring about a wholesome concentration of the mathematico-physical sciences, now threatened with a plethora of erudition. The insistence of older writers upon the organic character of the content of instruction deserves earnest consideration. [가르침의 내용의 유기적 특성에 대한 더 오래된 저술가들의 주장은 진지한 고찰을 할 만한 가치가 있습니다.] For the purpose of concentration a mere packing together of uncorrelated subjects will not suffice; their original connection and dependence must be brought into clear consciousness. Hugo's admonition also, to distinguish between hearing (or learning, properly so called) on the one hand, and practice and invention on the other, for which there is good opportunity in grammar and mathematics, deserves attention. Equally important is his demand that the details of the subject taught be weighed — trutinare, from trutina, the goldsmith's balance. This gold balance has been used far too sparingly, and, in consequence, education has suffered. A short-sighted realism threatens even the various branches of language instruction. Efforts are made to restrict grammar to the vernacular, and to banish rhetoric and logic except so far as they are applied in composition. It is, therefore, not useless to remember the "keys". In every department of instruction method must have in view the series: induction, based on sensuous perception; deduction, guided also by perception, and abstract deduction — a series which is identical with that of Plato. All understanding implies these three grades; we first understand the meaning of what is said, we next understand inferences drawn from sense perception, and lastly we understand dialectic conclusions. Invention has also three grades: we find words, we find the solution of problems, we find thoughts. Grammar, mathematics, and logic likewise form a systematic series. The grammatical system is empirical, the mathematical rational and constructive, and the logical rational and speculative [문법 체계는 경험적이고, 수학적 체계는 이성적이고[즉, 이해력(understanding) 및 의지력(willing)이 통제하고] 건설적이며, 그리고 논리적 체계는 이성적이고[즉, 이해력(understanding) 및 의지력(willing)이 통제하고] 사변적입니다.] (cf. O. Willmann, Didaktik, II, 67). Humanists, over-fond of change, unjustly condemned the system of the seven liberal arts as barbarous. It is no more barbarous than the Gothic style, a name intended to be a reproach. The Gothic, built up on the conception of the old basilica, ancient in origin, yet Christian in character, was misjudged by the Renaissance on account of some excrescences, and obscured by the additions engrafted upon it by modern lack of taste (op. cit., p. 230). That the achievements of our forefathers should be understood, recognized, and adapted to our own needs, is surely to be desired. (이상, 발췌 및 일부 문장들에 대한 우리말 번역 끝).

[내용 추가 일자: 2025-01-31] 게시자 주: 다음의 주소에 접속하면, 본글에 이어지는 글을 읽을 수 있습니다: http://ch.catholic.or.kr/pundang/4/soh/1423.htm [제목: What is Art? What is an artist? 외; 게시일자: 2013-07-27]

0 1,803 2 |